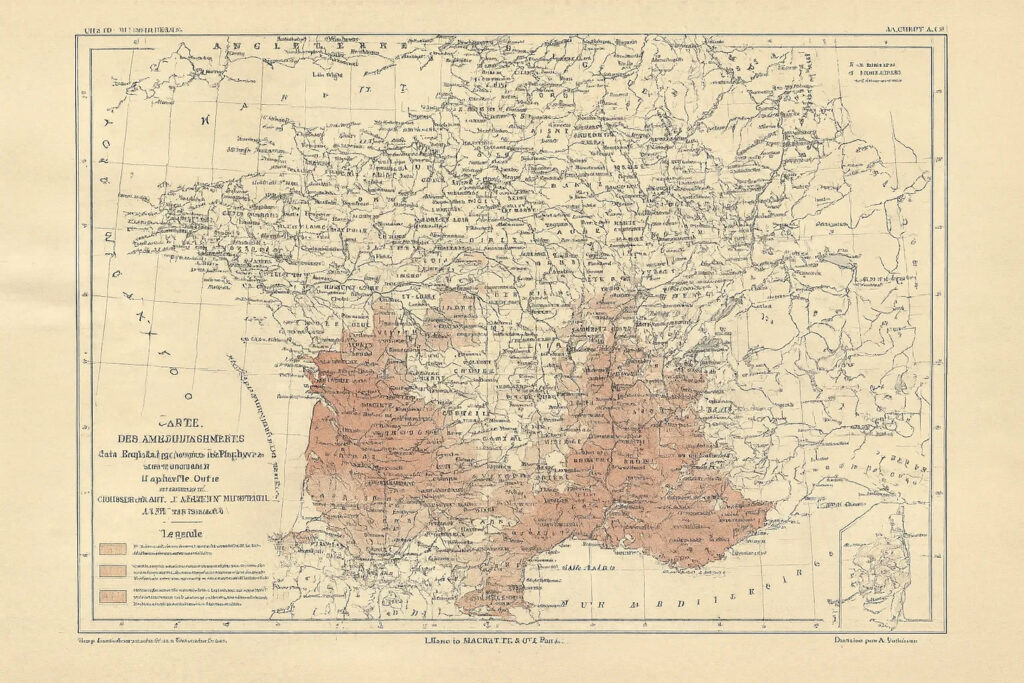

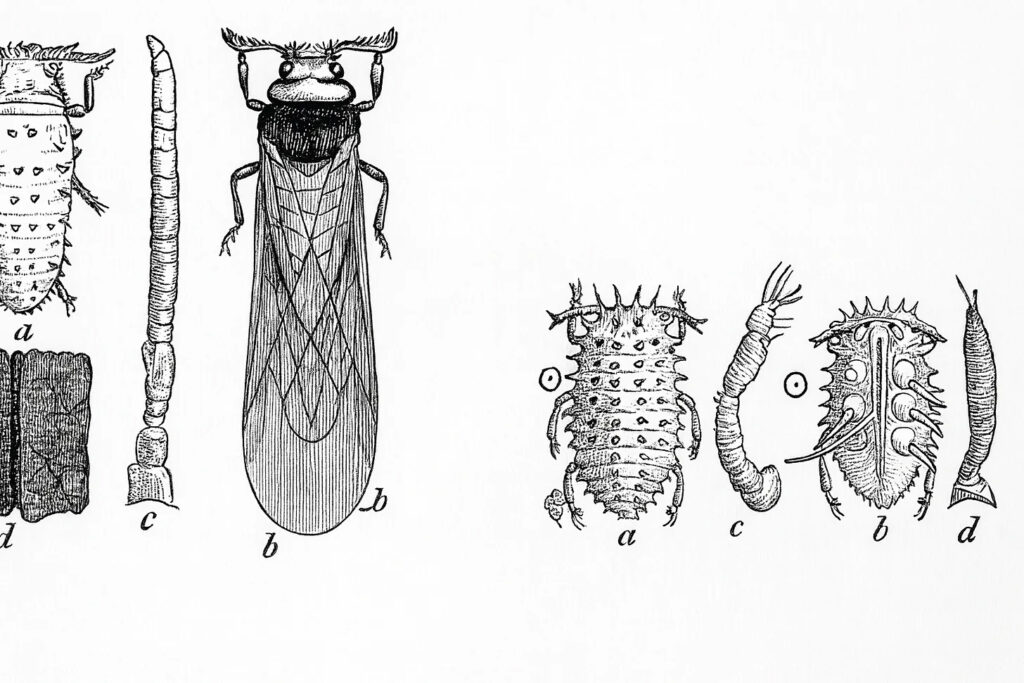

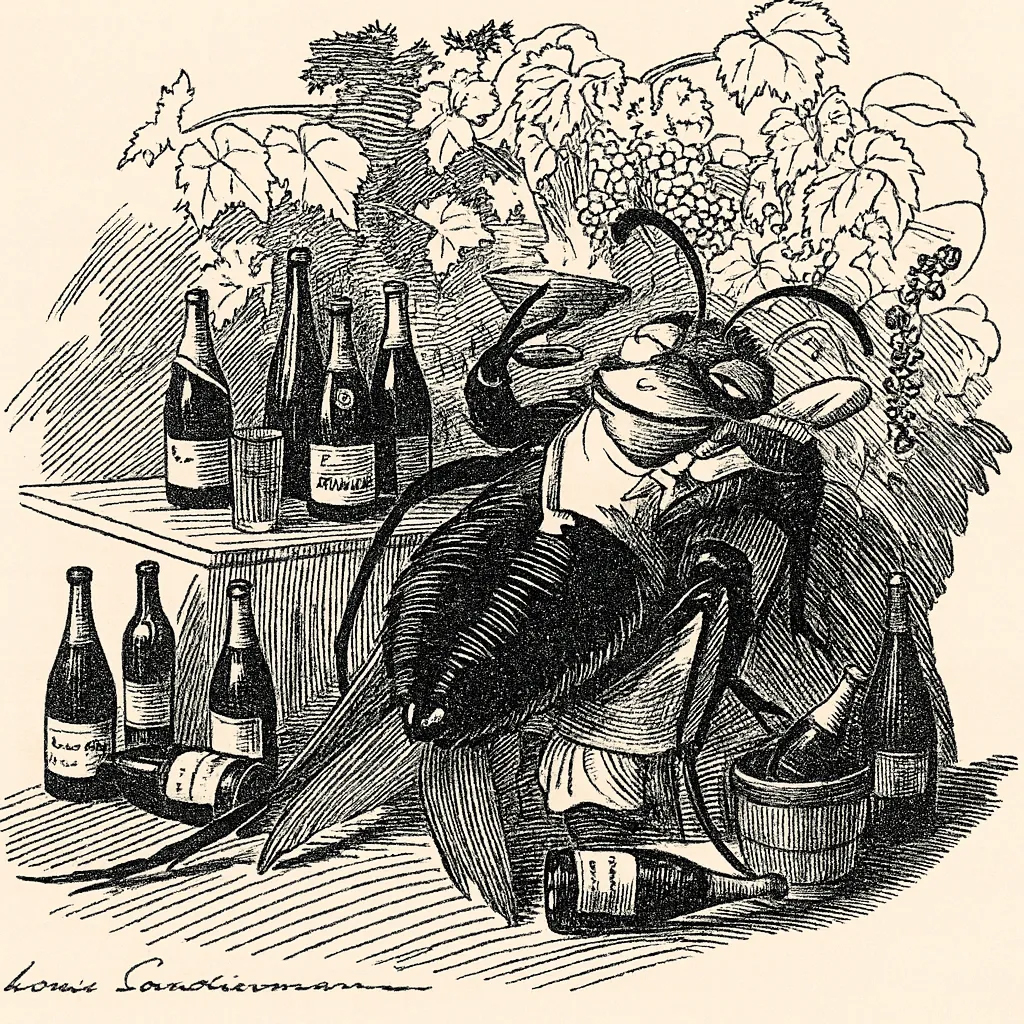

Summer, 1887. A delegation of French wine specialists appointed by the government lands in the United States. Their mission: to find information that will help bring an end to the Great French Wine Blight, which has seen almost half of the country’s vineyards ravaged by phylloxera vastatrix – an aphid-like pest that poisons and feasts on the roots of grapevines.

Since the blight began in the early 1860s, there has been a 70% decline in production. Counterfeit wines made from raisins and previously unseen labels from elsewhere in Europe flood the market, symptomising the disarray. There are 30,000 gold francs on offer from the government for anyone that finds a solution.

Growers have tried all kinds of remedies to resist the rot – from the scientific to the superstitious. Some resort to burying live toads under the vines to draw out the poison; others employ marching bands to play to their crops in the vain hope that the vibrations will deter the pests. Across rural communities, the scourge is widely understood to be the work of God; punishment for the perceived moral decay and growing secularism of French society.

The delegation represents one last shot at salvation and hopes back home are high. Its leader, a young botanist named Dr. Pierre Viala, sends regular bulletins back to France, which are published in the journal Le Progrès Agricole et Viticole. At first, his missives are humdrum – the delegation’s immediate concern is finding land with a similar soil composition to that of wine-producing regions in France, in the hope that this will provide some clues. But suddenly the tone shifts.

“I have interesting facts, but I cannot violate things by letting you know these official secrets,” Viala writes.

The precise point on the journey at which Viala wrote those words is uncertain. What we do know is that his fact-finding mission took him to the door of a mysterious Swiss immigrant living in The Ozarks named Hermann Jaeger. An encounter that was to change the course of European wine forever.

– – –

Hermann Jaeger was born in Brugg, Switzerland, in 1844. After leaving school and working for a wine business in Geneva, he emigrated to the US in 1864 and took up residence on a farm just outside of Neosho, Missouri. He was followed by his brother, John, who purchased the farm next door.

The pair arrived into a wine scene that was already flourishing. Local growers, who had long since abandoned the idea of planting French vines after discovering they were ill-suited to the soil, were finding success with native grape varieties. In 1851, Missouri winemakers won eight of the twelve medals on offer at the International Wine Fair in Vienna. In fact, many historians believe it was this event that triggered the phylloxera outbreak in the first place. The theory goes that in the aftermath of the fair, French winemakers took to importing and experimenting with American grapes, and inadvertently introduced the aphid.

After establishing the farm, the Jaegers naturally fell into complementary roles. John took care of the farming; Hermann, the growing of grapes. His work was to provide a breakthrough for the French, but not before he had overcome a blight of his own. In 1866, after grafting Concord and Virginia vines from the East Coast onto native rootstock, a downy mildew took over the vineyard and threatened to destroy the brothers’ plan to open a winery at its inception. Hermann found an innovative solution, spraying the crop with a blend of sulphur, iron sulphate, and copper sulphate – in doing so, pioneering the use of pesticides that we see today.

Undeterred, Hermann Jaeger spent the next couple of decades experimenting with rootstock and scouring the local countryside for unheralded grape species. This research helped to create around a hundred new grape varieties, with Jaeger lauded in wine circles for his success in cultivating hardier American vines that could withstand mildew and pests.

Though somewhat of a recluse, Jaeger was a frequent contributor to wine journals in this period and kept up correspondence with his peers. One of his closest confidantes was the Texas-based scientist Charles Volney Munson, who he named a grape variety after before it became more widely known as the Jaeger 70. Like Jaeger, Munson – though reportedly a teetotaller – had dedicated himself to cataloguing American grape varieties and experimenting with rootstock.

When Dr. Pierre Viala turned up in the US, he was advised to visit them both. Jaeger had the answer he was looking for. Some years earlier, he had raised phylloxera-resistant vines with a Missouri-based entomologist (the term for those who study insects) named George Hussman.

The idea of grafting French vines onto American rootstock wasn’t new. But it was controversial. Wine was not only a cornerstone of the French economy but its national identity, too. For many in France, to accept vines from the New World would be to admit defeat.

Nevertheless, after spending a couple of weeks with Jaeger on his Missouri farm and visiting Munson in Denison, Texas, Viala was clear that this was the only way forward. Upon his recommendation, the French government purchased seventeen boxcars of rootstock from Jaeger (plus more from Munson) and shipped them to the winemakers most in need of succour. Slowly, the industry began to recover and both Jaeger and Munson were awarded the French Legion of Honour. To this day, the vast majority of French wines are made from vines grafted onto American roots.

But Jaeger’s story doesn’t end there. Just a few years after that pivotal meeting with Viala, his fortunes changed with the passing of a local law which banned the sale of alcohol in his home county. The Prohibition era had begun and after a string of unsuccessful attempts to circumvent the law, Jaeger, his second wife, Elise, and their four children were forced out of Neosho.

On May 16th, 1895, Jaeger vanished completely. A few days later, Elise received a letter. Translated from German, it read:

“My Dear, Good Elise: When you read these lines, I won’t be no more alive. The more I think over everything, the more my mind get troubled. It is better I make an end to it, before I get crazy. Since for a length of time I am not able to attend to business… Do not hunt for me. I hope to end some place where nobody can find me. Dear Elise, you deserve better luck. I hope you will have it yet. Kiss the children. Your unlucky Hermann.”

As per his wishes, Jaeger was never found. And yet every single drop of wine produced in France and beyond is testament to his considerable, if largely unheralded, legacy.

By Isaac Parham